Why Vertical Integration Wins: A Software Engineer's Case for Owning Your Stack

I used to listen to Tesla Daily religiously. Every morning, Rob Maurer's voice walking me through the latest updates on battery chemistry, manufacturing innovations, and yes—vertical integration. Then came the X.com acquisition, and honestly? I got burnt out on all the noise.

But when I bought a car, what stuck with me wasn't the hype. It was the engineering lesson: vertical integration isn't just automotive strategy—it's competitive advantage.

And as a software engineer who's been online since AOL, I chose Tesla for one simple reason: I can't find the seams.

The Strategy That Survived the Noise

When Twitter drama drowned out engineering discussions, I stepped away from tracking Tesla and Elon. But sound engineering principles work regardless of noise. The vertical integration I learned about in 2018-2021 didn't stop being brilliant because of social media chaos—time validated it.

Vertical Integration vs. Assembly

Companies that control their stack: Apple (silicon, OS, retail), Netflix (content, streaming tech, algorithms), Tesla (batteries, software, manufacturing, sales).

Companies that assemble: Traditional auto makers (80%+ outsourced components, dealer networks), traditional media (licensed content, third-party platforms), traditional tech (commodity chips, generic OS).

The difference is architectural—and it determines who controls the user experience.

I Can't Find the Seams

After 25 years online, I can always spot the boundary between systems. The UI shifts, interaction patterns change, quality jumps or drops.

But in truly integrated systems? No seams.

My Tesla preconditions the battery for charging, and the same thermal stack manages cabin temperature. Set climate to 72°, the system doesn't differentiate between "keep battery optimal" and "keep human comfortable"—it's one integrated system.

This is what happens when you control the stack: you decide where abstractions live.

The "No One Owns This Problem" Problem

Assembly-based systems have blame boundaries:

Frontend blames Backend. Backend blames CDN. CDN blames origin. Meanwhile, users leave because the page takes 30 seconds to load.

When VW's infotainment crashes, the dealer says it's Bosch. Bosch says it's integration. Software says it's hardware. Six months, no fix. Two years later, still no fix.

Tesla eliminated this. Charging issue? They pushed an update to the entire fleet. One team owns charging hardware, software, payment processing, and the app.

The Scope of Tesla's Integration

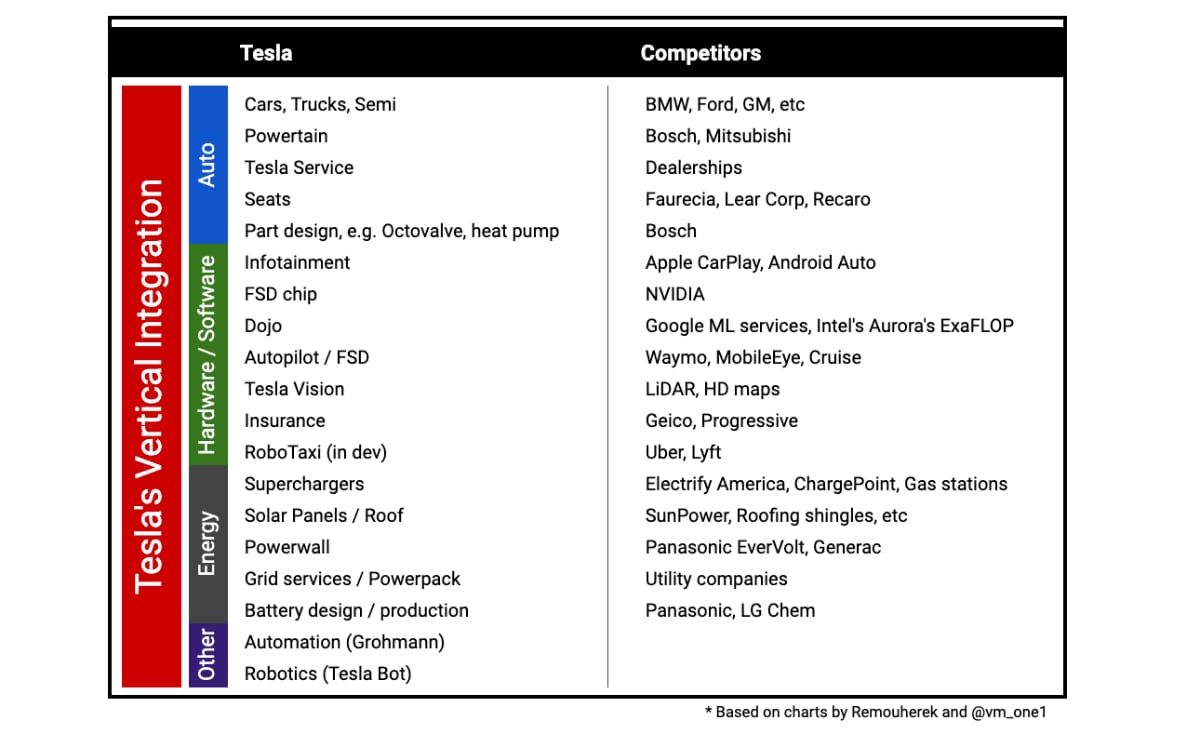

NotATeslaApp's breakdown shows how far this goes:

Chart credit: NotATeslaApp

Chart credit: NotATeslaApp

What this chart reveals:

Tesla's approach spans four major categories:

- Auto: Everything from the car body to powertrains to service

- Hardware/Software: Custom chips, FSD software, infotainment systems

- Energy: Solar panels, Powerwalls, grid services, battery production

- Other: Insurance, robotics, automation systems

Traditional competitors rely on external vendors for:

- Critical software components (Apple CarPlay, Android Auto instead of custom systems)

- Core hardware (NVIDIA chips instead of custom silicon)

- Manufacturing equipment (Bosch, Continental suppliers)

- Sales channels (dealership networks instead of direct sales)

This isn't just about making more components in-house—it's about controlling every layer of the technology stack. As Elon Musk described it, "Tesla is a chain of startups," each focused on a specific piece of the integrated experience.

The result? When I drive to San Francisco, the car automatically preconditions the battery 20 minutes before I hit the Supercharger. When I get there, the charging port opens as I walk up, and the car starts charging without me touching anything. The nav system already factored in my driving style, the weather, and the charging curve to route me to a station that'll be ready when I arrive.

One Codebase, One Quality Standard

The Tesla app uses the same APIs as the car's touchscreen. Fix a charging bug, it's fixed everywhere simultaneously.

Traditional automakers: mobile app from one vendor, infotainment from another, navigation from a third. Each has different bugs, update schedules, and definitions of "low battery."

In my Tesla, state-of-charge means the same thing in the app, dashboard, charging screen, and Supercharger network. One codebase, one battery management system.

Why This Matters for Engineers

Same reason I choose monorepos over microservice chaos: control over abstraction layers means optimizing for user problems, not vendor limitations.

Tesla treats cars like software:

- Continuous deployment: Bug fixes to millions of cars overnight

- Shared state: One source of truth for battery charge, location, preferences

- End-to-end testing: Changes verified from app to charging hardware

Traditional automakers ship software like it's 2005—CDs, isolation, prayer.

The Engineering Decision

I bought Tesla because I recognize good architecture.

Full stack control—battery cells to mobile app—enables decisions impossible in assembled systems. Optimize charging curves based on real-time temperature data, update the algorithm fleet-wide overnight.

Try that with LG Chem batteries, Bosch software, Accenture's app, and Electrify America's network.

After 25 years debugging integration problems, driving a unified system is remarkable.

That's what vertical integration gets you: the ability to engineer solutions instead of engineering around limitations.

What's your experience with integrated vs. assembled systems in your industry? Have you found opportunities to take more control over your customer experience? I'd love to hear about your wins and challenges in building cohesive systems.

Beyond API Wrappers: Building State-Driven MCP Servers for Long-Horizon Agent Orchestration

Explore how MCP servers can move beyond simple API wrappers to become sophisticated state machines that orchestrate complex, multi-phase projects with specialized agent teams

The Min-Maxer's Trifecta: Building Tools for the Game You Actually Play

How building tools for Last Epoch lets me combine software development, gaming, and guilt-free relaxation into one satisfying loop.